Hugo is one of those movies that does multiple things at once. Upon its release, it was touted as Martin Scorsese’s first family film that also happened to be a masterpiece. But when you look a little deeper, it does something more. This movie was an opportunity for two lovers of cinema to meet and to share a story together. Brian Selznick, the author of “The Invention of Hugo Cabret,” the book which preceded Scorsese’s film was written by someone who also looks to the history of cinema to inspire his own stories. So, it would seem fitting that an American master of the art form would take up its adaptation, finding in the character Hugo a kindred spirit.

The film opens with a sweeping CG shot of 1930s Paris, giving the audience all at once a sense of time, place, and style with the visuals throughout the film borrowing heavily from the steampunk aesthetic. As we are escorted through the train station, we are introduced to our chief pair of central characters: Georges Méliès (Ben Kingsley), a stately gentleman with a handlebar mustache, a bald spot, and hair that has long since been washed gray with age manning his toy booth and Hugo Cabret (Asa Butterfield) excitedly peering out into the world of the train station from behind one of the clocks that he maintains. The story follows the young orphaned clock works expert who lives in a world within the walls of the train station as he steals both to survive and to find the final piece necessary to unlock the mystery of the automaton left to him by his late father. In a quest to retrieve the notebook left to Hugo by his father, Hugo befriends Isabel (Chloe Grace Moretz) as the two become fast friends while simultaneously exchanging with one another their love of adventure, imagination, and escapism; Isabel through books and Hugo, through the medium of film.

It is through this journey of discovery that they uncover the startling revelation; the man known affectionately as Papa Georges is none other than cinematic pioneer Georges Méliès. It is here where the movie shines. Through the magic of modern-day cinema, we are transported back in time to see the birth of special effects as well as the burgeoning of narrative film. We are shown re-creations of some of Méliès’ best-known works as he recounts an amorous affair with budding technology being transmuted into an art form, colliding head-on with postwar social upheaval, and ultimately ill-fated results. From this point forward, the theme of the movie is laid bare: the cathartic power of cinema. Through Hugo, Scorsese allows us to see into a childhood that is little-known; the story of a sickly child looking out into the world through his first viewfinder, constructing his own movies in the world of his imagination. Scorsese’s first foray into the world of family films is a tender love letter to the endeavor that has given him a career, a pathway to self-healing, and a family that he never thought he would have. Simultaneously, it rights one of the greatest wrongs in film history and places Georges Méliès square at the center of the pantheon of great filmmakers upon whose shoulders all of us behind the camera can stand firm and tall. This is an ode to Méliès for cinephiles and their families to revel in. Regarding Méliès work as seen in this film, Roger Ebert once wrote,” We see Méliès (who built the first movie studio) using fantastical sets and bizarre costumes to make films with magical effects — all of them hand-tinted, frame by frame. And as the plot makes unlikely connections, the old man is able to discover that he is not forgotten, but indeed is honored as worthy of the Pantheon.” Indeed, Méliès and his reputation are finally where they belong: out of the pages of film studies textbooks and brought to life for everyone to enjoy and admire no matter how old they might be.

Man is a curious animal. He is uneasy in the face of great experiences, and if he is forced to experience something profound, he starts immediately to cheapen it, to bring it down to his own level. Thus after a great man is assassinated, lesser men immediately manufacture, buy and sell plastic statues and souvenir billfolds and lucky coins with the great man’s image on them.”

Man is a curious animal. He is uneasy in the face of great experiences, and if he is forced to experience something profound, he starts immediately to cheapen it, to bring it down to his own level. Thus after a great man is assassinated, lesser men immediately manufacture, buy and sell plastic statues and souvenir billfolds and lucky coins with the great man’s image on them.” It pulled me into the desert as I watched my species ancestors go from simple apes to tool-using and intelligent, ingenious creatures, to men who looked like me, and whose creations dwarfed them by several orders of magnitude. I was watching the history of my species unfold into a future that still has yet to be. But all at once, I could see the echoes of that fictitious future in my own reality. Commercial space travel in this future has become so mundane, so commonplace, that the protagonist sleeps rather than being at all impressed with his surroundings. This is clearly something he’s done many times before, and something I suspect that our successors on this planet will see in their still unborn lifetimes. I was enveloped by the blackness of space and held utterly in its vastness. I felt small but oddly proud at the same time. And I came away with my own understanding of the film, not one borrowed from people far more brilliant than mine. After all, it only took me 16 years of watching this movie for that to finally happen.

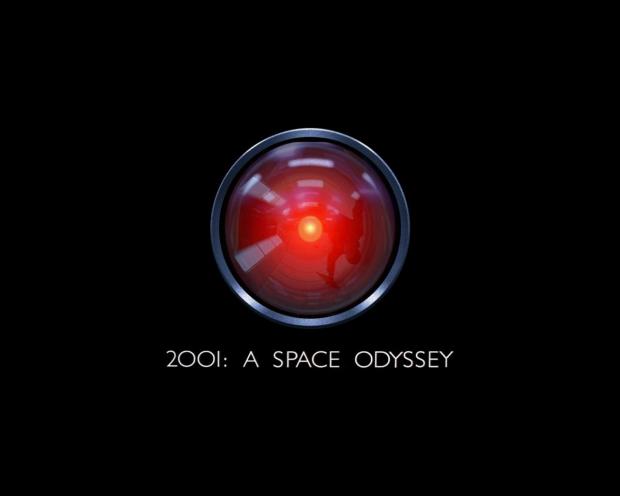

It pulled me into the desert as I watched my species ancestors go from simple apes to tool-using and intelligent, ingenious creatures, to men who looked like me, and whose creations dwarfed them by several orders of magnitude. I was watching the history of my species unfold into a future that still has yet to be. But all at once, I could see the echoes of that fictitious future in my own reality. Commercial space travel in this future has become so mundane, so commonplace, that the protagonist sleeps rather than being at all impressed with his surroundings. This is clearly something he’s done many times before, and something I suspect that our successors on this planet will see in their still unborn lifetimes. I was enveloped by the blackness of space and held utterly in its vastness. I felt small but oddly proud at the same time. And I came away with my own understanding of the film, not one borrowed from people far more brilliant than mine. After all, it only took me 16 years of watching this movie for that to finally happen. For me, HAL 9000 represents a couple of things: the first and most obvious one is a trope that gets recycled more often than I would ever like to see in symbolizes our dependence on technology and what can happen when we reach that extreme. The other is a bit subtler. HAL represents the point at which our environment becomes able to overtake us. It’s at that point where our adaptations via the machinations that we have built in order to conquer environment outstrip our ability to control them. And of course, we know that eventually HAL is disconnected, Dave’s character undergoes what I can only term as the greatest non-psychedelic induced psychedelic journey I have ever been on. He meets himself, and on his deathbed he is reborn a cosmic infant causing me to ponder Nietzsche’s eternal recurrence; the patterns and impressions on the psyche and cycle of time that seem to repeat themselves as if it happened before, but often changing in subtle ways that cause us to feel the need to reconsider our lives, their meaning, our place in the universe, our relationship to technology and to other people. It is these types of questions that spawned from the mystery of the monolith, and the movie that delivered them to me on this fateful day has caused me to fall in love with cinema with fresh eyes and a renewed joy. And when you find something like that, whatever it is, enjoy it, love it just as you would another person, and share that with someone else.

For me, HAL 9000 represents a couple of things: the first and most obvious one is a trope that gets recycled more often than I would ever like to see in symbolizes our dependence on technology and what can happen when we reach that extreme. The other is a bit subtler. HAL represents the point at which our environment becomes able to overtake us. It’s at that point where our adaptations via the machinations that we have built in order to conquer environment outstrip our ability to control them. And of course, we know that eventually HAL is disconnected, Dave’s character undergoes what I can only term as the greatest non-psychedelic induced psychedelic journey I have ever been on. He meets himself, and on his deathbed he is reborn a cosmic infant causing me to ponder Nietzsche’s eternal recurrence; the patterns and impressions on the psyche and cycle of time that seem to repeat themselves as if it happened before, but often changing in subtle ways that cause us to feel the need to reconsider our lives, their meaning, our place in the universe, our relationship to technology and to other people. It is these types of questions that spawned from the mystery of the monolith, and the movie that delivered them to me on this fateful day has caused me to fall in love with cinema with fresh eyes and a renewed joy. And when you find something like that, whatever it is, enjoy it, love it just as you would another person, and share that with someone else.